A blog for Catholic men that seeks to encourage virtue, the pursuit of holiness and the art of true masculinity.

Calvary: A Film for Our Times

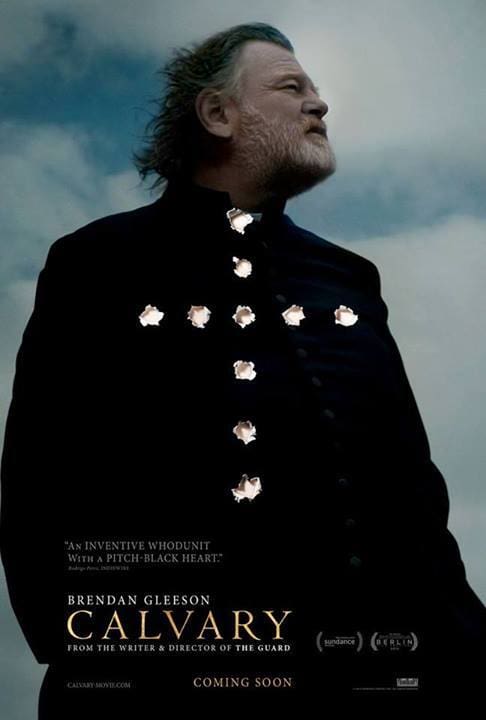

The following is a review of the film Calvary. Spoilers Ahead. Calvary is rated R and earns this rating. Viewer discretion advised.

I first watched the film Calvary four years ago. I remember leaving the theater feeling shocked and not a little disgusted. It was a brutal film, even an ugly film. And yet, four years later, I believe it is exactly the film we need right now.

A Good Priest is Hard to Find

Calvary follows a week in the life of Father James (Brendan Gleason), a parish priest in rural Ireland. Father James is an aberration of sorts, a traditional priest in a modern church. He is a late-in-life vocation who pursued the priesthood after his wife’s untimely death. He wears a cassock, hears confessions, dispenses advice, and celebrates Mass, striving to be as faithful as he can—all the while receiving little or no support from his feckless, weak, and worldly bishop.

The film opens with a bang. Father James in the confessional hearing the confession of an anonymous penitent. The penitent is not there to confess his sins, however, but rather to threaten Father James. He confesses that he was raped by a priest, and now someone must pay for his suffering. He tells Father James that he will be killed in a week, and that he must make his final arrangements before his death. He also makes it clear that he is targeting Father James, not because he is a bad priest, but because he is a good one.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The rest of the film follows Father James’ final week, and what a week it is.

He counsels a boy seeking direction. He comforts the grieving. He offers last rites for the dying. He counsels a brutal murderer in prison. He reaches out to the lost sheep—parishioners who have stopped coming to Mass or who have a reputation for sin. In short, he practices all the spiritual and corporal works of mercy with genuine care and goodness.

Meanwhile, his drug addicted daughter, Fiona, arrives after a failed attempt at suicide. She feels abandoned by her mother’s death, and resents her father for choosing the priesthood. She is bitter and angry and feels she can never find it in her heart to forgive.

Yet, for all his suffering, Father James sees little or no fruit from his labors. Everywhere he meets with the brutal ugliness of sin and the terrible reality of evil. Everywhere he is mocked, tempted, humiliated, and spit upon, despite his best efforts to be a genuine Father to his people.

Father James struggles to face his trials stoically and courageously. But when his parish church is burned to the ground by a hateful arsonist, he is devastated.

Father James can bear no more. He removes his cassock and dresses like a layman. He heads to the nearest bar to get drunk, but while there, he meets an evil characters who, to torment him, describe the suffering of a child with such horrific detail that Father James snaps. He fires his gun into the bar, but in turn is beaten to a pulp by his tormenter.

Father James seeks to recuperate at home, but only receives further blows. His weak and simpering assistant priest, who has done little but whine, can’t bear the pressure of persecution and abandons the parish and Father James.

All Father James can think of is escaping the priesthood as fast as he can. He decides to leave, but at the last minute sees a grieving widow he comforted, and realizes there is more work to do. He returns to the clerical state and returns to his parish to meet his fate.

Without Sacrifice, There is No Love

The film culminates on the beach by the sea. Father James throws his gun, which he had kept for self-defense against his murderer, into the sea. He is ready for whatever may come.

In the final climactic scene, he is faced by his accuser who pours out all his bitterness, pain, and hatred. I will not reveal what happens next, but I will simply say that the ending is powerful, shocking, and indeed, appropriate. Through sacrifice, healing and reconciliation occur in the midst of suffering.

A Film for Our Times

News of the horrors perpetrated and covered up by clergy dominate the headlines of late. And I fear this is only the beginning of what will come to light. We must be honest and face facts: Evil has infiltrated the Church, and wicked men have shattered thousands of lives in a quest to sate their demonic lust.

In such a climate, triumphalist, prideful, shallow, and superficial Catholicism cannot survive. For too long, we’ve lived in an atmosphere of cheap grace. We’ve embraced a Catholicism without the cross. We chatter incessantly about mercy and forgiveness, without ever talking about sacrifice, contrition, atonement, or penance. But such cheap grace, such easy faith, is not reality. It’s an illusion, even a dangerous delusion.

There can be no healing from this crisis without atonement. Statements, documents, and policies will not save us. On the contrary, we must be prepared, like Father James (and even Christ himself), to face the terrible calvary of humiliation, derision, and rejection. We must be prepared to be spit upon and hated, justly or unjustly, when we seek to do good. We must be prepared to be lambs among wolves. But more importantly, we must be prepared to look evil squarely in the face, in all its horror and ugliness, and overcome it with goodness and love. Such suffering will be real, a small penance for the evil perpetrated in the name of Christ, but we cannot run from the cross.

Calvary is an ugly film, but a powerful one. Its message is that of love triumphing over evil, of a shepherd who choses to lay down his life for his sheep. Its message is that the good must suffer to atone for the evil; that we should talk more about virtue than about sin; that “forgiveness has been highly underrated.” And perhaps most importantly, its message is that, in the words of Father James, “the limits of His mercy have not been set.”

Good review. I’ve wondered for years why despite my best efforts everything I did seemed to go awry for the smallest reasons. It seemed like I was not allowed to have or enjoy anything that this life offers. But then I figured it out. Christ was mocked and ridiculed very shortly after his triumphant appearance into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. In a few short days he would be convicted falsely and given the capital punishment of those times. Talk about getting “hooked up” by the very system that He came to fulfill. It doesn’t seem right. And I said that about my own circumstances. But then I began to pray earnestly with the Divine Mercy Chaplet and then the Rosary. I concluded that I am suffering in this life because I believe deeply in Jesus and the promise of the life to come. So this suffering is not so ignominious after all. It means that, dare I say this, I’m following Christ’s footsteps, albeit precariously. It’s a work in progress.

The film play must have been written by someone who understands the complex nature of relationships with God.

Indeed John Murphy. God bless you.

I’d never heard of this film (but my non-Catholic husband had) so we watched it together. The brutality and crassness of it put me in a constant state of wincing, but it is an unforgettable film and beautifully done, as The Catholic Gentleman says “there can be no healing from this state without atonement”.

A good argument against a widower entering the priesthood. A Father will be a parent to his children no matter how old the children are. God forbid that my wife should precede me in death, but I cannot see a time where one of my twelve children would not benefit from my help. I couldn’t do that if I were a priest.