[…] post Art for God’s Sake: An Interview with Artist Daniel Mitsui appeared first on The Catholic […]

A blog for Catholic men that seeks to encourage virtue, the pursuit of holiness and the art of true masculinity.

Art for God’s Sake: An Interview with Artist Daniel Mitsui

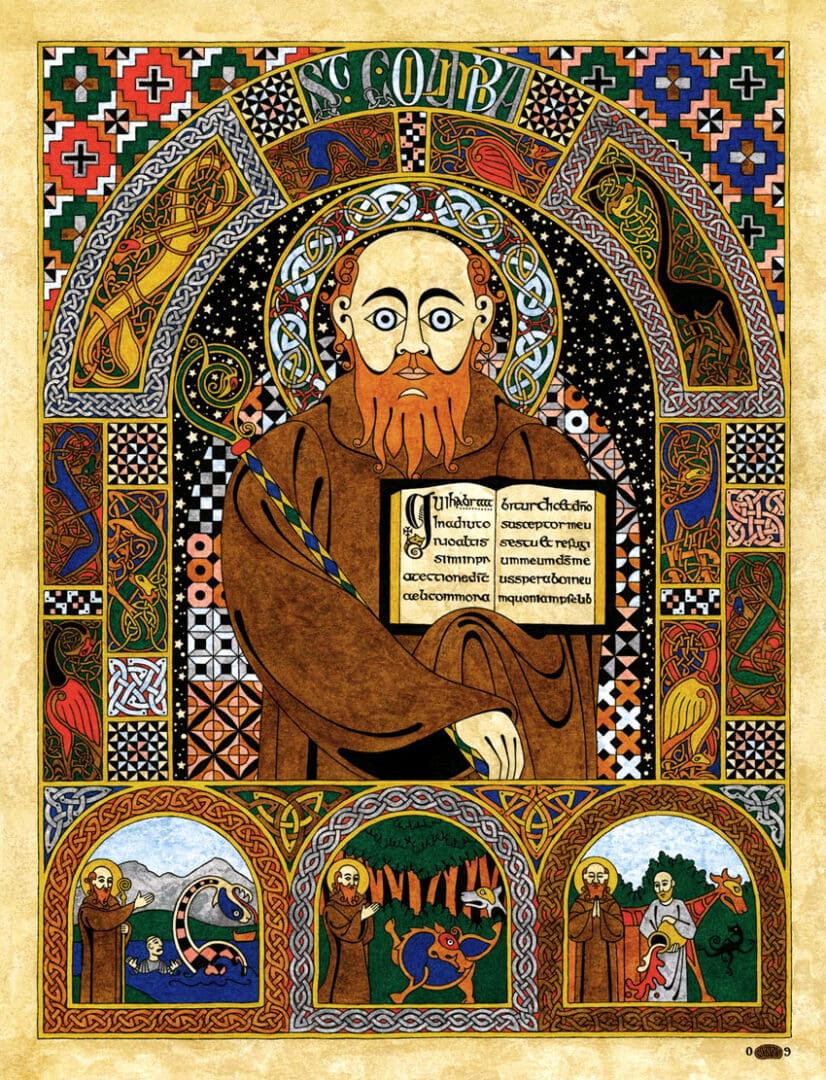

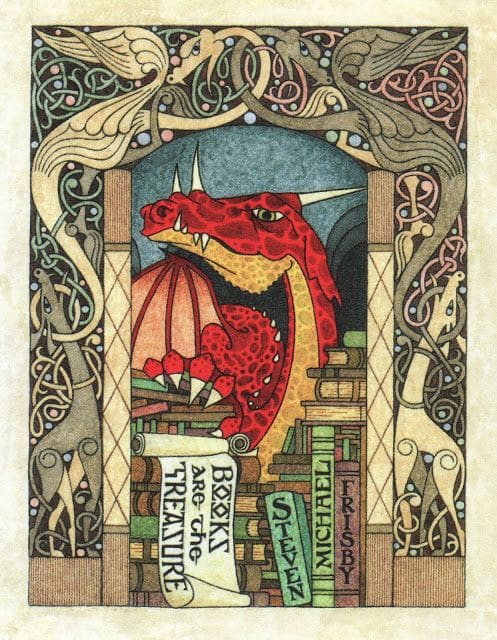

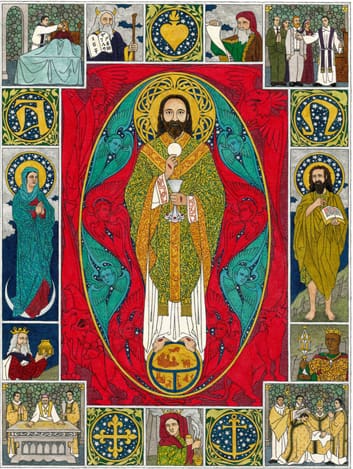

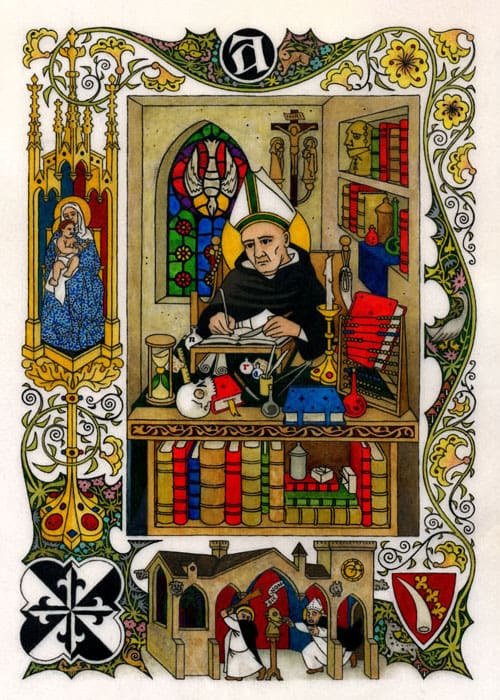

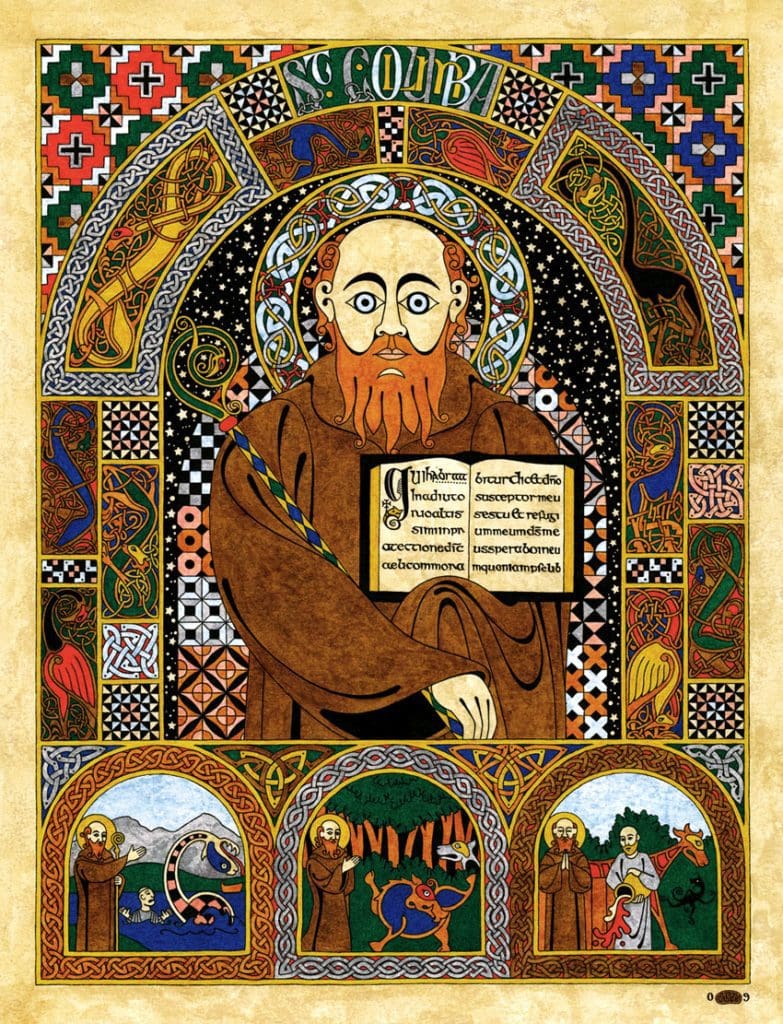

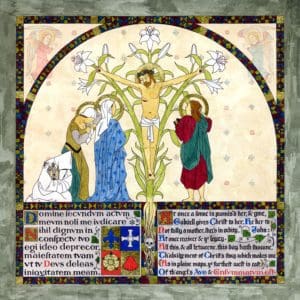

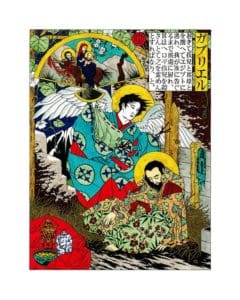

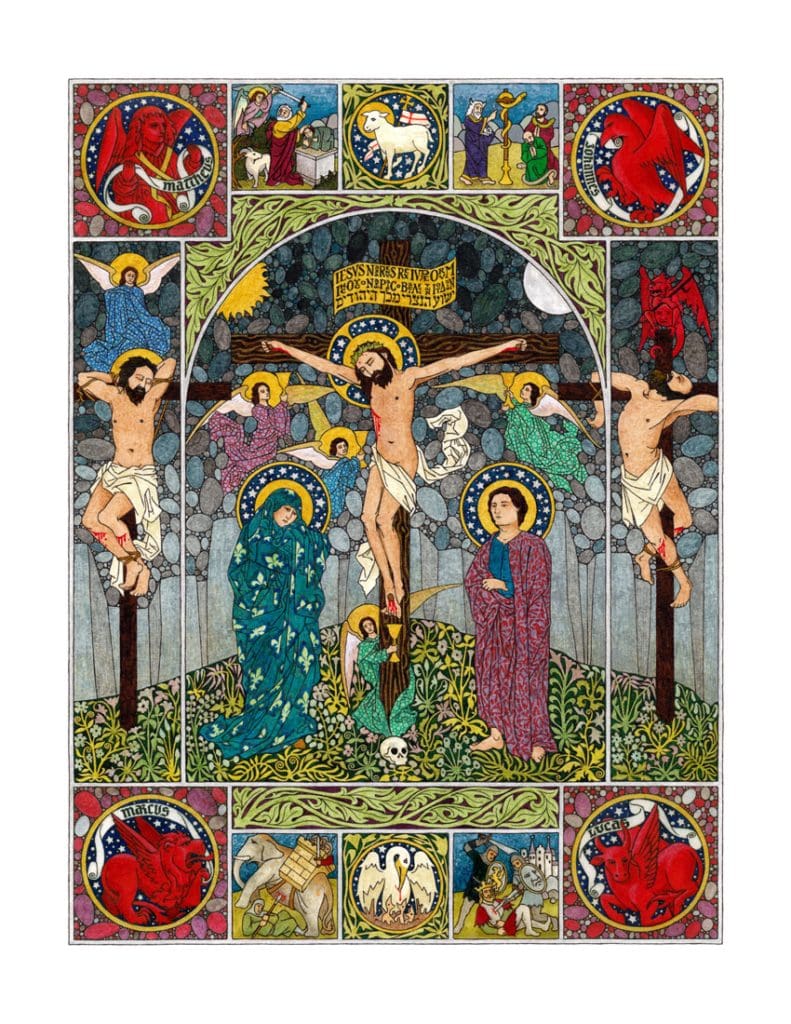

For years now, I have been captivated by the stunning work of Catholic artist Daniel Mitsui. Daniel is a master of his craft, illuminating manuscripts with the same skill and attention to detail as the great medieval artists. His work is both bold and intricate, and it leaps to life with vibrant colors and commanding figures. It is at once traditional and freshly contemporary, a combination that makes it truly unique.

Recently, I approached Daniel for an interview, and he was gracious enough to take time from his busy schedule to answer a few questions about his conversion to Catholicism, how he learned his craft, what inspires his work, and more. (All images can be clicked on for larger versions)

1. You are a convert to Catholicism. Conversion stories are rarely brief, but can you share a little bit about how that happened?

I am a convert in the sense that I was not baptized, and did not regularly attend Mass, until I was an adult. However, I did not really convert from anything; I was never an unbeliever, a Protestant or an adherent of a different religion. From my earliest memories, I always had faith and thought of myself as a Catholic. I do not have a natural explanation for why that was so.

My late father had been raised a Baptist, but did not profess any faith during the years of my childhood. My mother had been raised Catholic; my parents had married outside the Church. Our home did have a crucifix on the wall and a Challoner Douay-Rheims Bible on the shelf (some of which I read privately); my family attended Mass on Christmas and Easter. I remember occasionally attending Mass on other Sundays.

Despite not having received the sacraments, throughout elementary and high school I told all of my friends that I was Catholic, and tried to defend the Church whenever some controversy arose in a classroom. I had, already, a deep fascination with medieval religious art and manuscript illumination. Perhaps it was best that my idea of the Church was formed more by history, art and scripture than by the typical parochial experience in the Chicago suburbs during the 1980s and 1990s.

Had I been a more courageous child, I would have sought religious initiation on my own, or demanded it; instead, I determined to seek it after leaving my parents’ house. But during my first few years away attending Dartmouth College, I was depressed and resisted my religious impulse. Eventually, I had to admit to myself that I could not remain indifferent and could not become anything other than Catholic; I contacted the priest on campus and went through the RCIA program at the student center. I was baptized and confirmed, and received my first communion, at the Easter Vigil in 2004, shortly before graduation.

It was inevitable that I would gravitate to the traditional Latin Mass; I was attending it exclusively (or very nearly so), and as a matter of principle, within a few years. I settled in Chicago. I met my wife in 2007; we married in 2008. So far, we have two sons and a daughter, and another child due to be born this summer.

2. How did you get started as an artist?

I have been drawing avidly since I was a small child. By the time I was 18, I knew that I wanted art to be my profession, and the first works I remember selling were things I made in college. I was not, then, a religious artist; I made drawings, paintings, prints and collages in a modern style heavily influenced by the surrealist art of Max Ernst. I became somewhat disaffected toward the culture of modern art, and decided against pursuing a career in galleries. For about two years, I delved into comic strips and film animation, and had a lot of fun studying and making these. At the time I left college, I saw two possible directions for my career, one toward comic art and the other toward religious art.

Obviously, I chose the latter. The next few years were transitional; now being an observant Catholic, I was more fascinated by medieval religious art than ever before, but my experience was almost entirely in modern art and in cartooning. My early religious drawings were hampered by this, and I do not consider most of them successful. I persisted though, and eventually the art improved. Until 2010 sold drawings and worked on commissions while working other jobs. By then, I was earning enough from art that I was able to make it my exclusive livelihood.

3. How does your faith influence your artistry?

Almost all of my drawings are religious in nature; aside from bookplate designs, I decline most secular commissions. When making religious art, I draw what I believe and I believe what I draw; I do not appropriate religious imagery for any ironic purpose. I believe that the events described in the Old and New Testaments really happened. When depicting hagiographic legends, I give the traditional stories the benefit of doubt whenever possible. The miracles described in Holy Writ establish my standards of credulity about what sort of things happen in the real world. Thus, when I draw St. Brendan celebrating Mass on the back of a whale, it is because I believe that this is something that can and did happen; certainly it is no stranger that the story of Jonah.

I often quote one of the fathers of the Second Council of Nicea, who said: The composition of religious imagery is not left to the initiative of artists, but is formed upon principles laid down by the Catholic Church and by religious tradition…. The execution alone belongs to the painter; the selection and arrangement of subject belong to the Fathers.

The Catholic tradition of religious art has a real and permanent content, just like the liturgical tradition and the theological tradition. While artistic tradition perhaps does not have so exalted a place in our religion as these, it corroborates them and operates with the same principles. Like these, it cannot be altogether remade or replaced without ruinous effect. Modern Catholics often have a confused notion of tradition, thinking of it in terms of what changes rather than what endures.

But Catholic tradition is based on real events; the things that Jesus Christ did and said that were heard and remembered and handed down. Something either is part of that tradition or it is not; if it is part of that tradition, this is evident in the law of worship and the agreement of the Church Fathers. It is a mistake to think that the only parts of tradition that matter are those that have found expression in magisterial documents. This is an epistemological absurdity; the bishops who are tasked with writing these documents need to know what they know somehow! Unless tradition has authority of its own to tell them what they must believe and must do even when they want to believe or do something else, it is a mere legal fiction.

And so, as a religious artist, I believe that my compositions must be traditional; if there is an established and consistent way of depicting some event, I must follow it. If there is not, then I must study the liturgy and patristic exegesis for guidance. Any liberty I take must be justified according to their principles.

4. You create a lot of sacred art. Do you have some favorite religious themes you like to incorporate into your work?

There is nothing that I enjoy drawing so much as the New Testament – the major events in the earthly life of Jesus Christ; in the lives of Mary, John the Baptist and the Apostles; or in the end times and Last Judgment. These events are the very stuff of Christianity, and I think I would be satisfied if I drew nothing else. Indeed, I have been making a long-term plan for my artistic career, a series of drawings that would summarize the New Testament. I hope to complete this over the next ten to twenty years.

One idea that is very prominent in my artwork – as it is in the liturgical tradition and in the exegesis of the Church Fathers – is that the Old Testament is an adumbration of the New Testament. Its events prefigure those of the Gospels. I usually research and include those prefigurements identified by Catholic theology and liturgy in my presentation of events from the Gospels.

5. Your art has a medieval influence. Yet, it is a style that is distinct and modern as well. How do you blend both old and new in your artwork?

As I said before, religious art must be traditional. I believe that the art called Gothic is fully traditional, the last art that did not predicate its originality on a rejection of the past. It is a summary of the iconographic traditions of the preceding ages, put into order and expressed more clearly than ever before – the visual equivalent of a high medieval encyclopedia. It is as complete and disciplined a system as Byzantine art, but aligned to the Latin liturgy and the Latin Church Fathers. This is why I make it the basis of my own artwork.

Gothic art was most theologically precise in the 12th and 13th centuries, so I defer to the art of those centuries for iconographic guidance; I especially value the art made under the direction of Suger of St. Denis, the metalwork of Nicholas of Verdun and Godfrey of Huy, the statuary and glass of the cathedrals at Chartres and Sens. But because I specialize in small, two-dimensional works of art, I often look to the following two centuries, in which the arts of manuscript illumination, panel painting, tapestry and printmaking culminated. It is in these later expressions of Gothic that I most often seek visual inspiration. Certain artists of later centuries admired Gothic art and understood aspects of it so well that I find their work as instructive as anything made in the Middle Ages. William Morris and Eyvind Earle are two that have had an especially strong influence on me.

I believe that a farsighted and generous consideration of beautiful forms is in the true spirit of Gothic art; this is one reason why it so quickly became established internationally. Its artists, while maintaing the iconographic and doctrinal integrity of the Christian tradition, admitted the influence of almost any beautiful thing they encountered. Oriental damasks and carpets, Mamluk metalware and pseudo-Kufic calligraphy all appear in Gothic art.

This was done, not in a spirit of cultural indifferentism, but in a spirit of giving God what He deserves, the very best we have to offer. The textiles of Mesopotamia and the platters of Egypt were fitting influences on Catholic art because they were the most precious and beautiful things of their kind that Catholic artists had yet encountered. To eschew them would be something of a cheat on God.

I too have an admiration for Islamic art, especially that of the Safavids, and its influence on my decorative art is ever increasing. Another decorative art that I study is Northumbro-Irish. (This was already adapted to Christian use in early medieval manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels.) Japanese woodblock prints have influenced my drawings. Really, there is no end of possibility here; every beautiful form can climb and flourish upon the theological framework of Gothic art.

I have begun to revisit even those things I studied before I turned to religious art. I am experimenting again with decalcomania, a technique most fully developed by Max Ernst. The great comic strip artists, especially Hal Foster and Winsor McCay, have given me good ideas lately. I do not consciously want my art to be modern, but I do want it to be lively.

6. You prefer working with ink instead of paint. Why do you prefer this medium?

I like to create works both in color and in black and white, and ink works well for that. Lately, I also have been drawing works with only the dark areas colored, the rest of left white, imitating the white-vine style of manuscript illumination.

There are practical advantages to ink drawing; it is not so messy that it requires a large, segregated studio space. And I like that my kids and pregnant wife can spend time in my studio without much worry about pigment toxicity. Having established the habit of drawing in ink, I have come to realize that the most important ideas that I want to depict can be depicted this way.

At present, I have enough business to draw in ink that I do not need to take the time and expense to train, practice and acquire the materials necessary to work in another medium. That is not to say that I have no interest in painting in oil on wooden panels, or engraving metal, or carving hardstone or boxwood or ivory; but I do not foresee doing any of this in the near future.

7. Your work incorporating Japanese influences is intriguing. How does your ethnic heritage influence your faith and artwork?

By blood, I am half Japanese; however, my cultural connection to Japan is not strong. My Japanese ancestors came to the United States about a century ago. My paternal grandparents and their siblings were all born in America; my father and his siblings never learned to speak Japanese.

My interest in Japanese art did not come through my family, but through my patrons. I received a commission from a priest whose religious order had done missionary work in Japan; he asked me to draw Saint Michael in the style of an ukiyo-e woodblock print. I had never done anything like this, had never thought to do anything like this. But I accepted the commission and I liked the result; so did my other patrons, who requested more and more of these transpositions of medieval iconography into the style of Japanese art.

It was in the course of doing research to compose these pictures that I came to admire the fantastic artistry of the ukiyo-e masters; I am especially impressed by the later masters such as Kuniyoshi and Yoshitoshi. It is not because they were Japanese, but because they were great artists, that I maintain an interest in their work.

More recently, I have become interested in another kind of Japanese art, one more properly religious: the Buddhist sutras written and illustrated in gold and silver ink on indigo-dyed paper. This tradition flourished in Korea as well. I plan to attempt something like this in the coming years.

I hope not merely to affect these styles on occasion, but to integrate the best aspects of them into all of my drawing. This I already am doing in subtle ways. For one example, I think that the Japanese printmakers’ treatment (or rather, non-treatment) of cast shadow is very satisfying visually. Following their example, I now eschew altogether shading by hatch. This allows me to avoid an excessively natural treatment of light that would disorient the sacred perspective of a religious picture.

8. Art has faded from the public square in the modern world. Many consider it the realm of intellectuals or elites. How can beautiful artwork help the average man and the average Catholic?

Many average people have gotten the idea – perhaps they have absorbed it from pop-cultural presentations of artists – that they are not capable of being either patrons of the arts or artists themselves.

Art patronage is a traditional way for those who are not artists themselves to assist the creation of art, and I expect that many people of average means assume that this is too expensive, without ever having investigated its cost. While I would not call any of my drawings cheap, they are comparable in price to tattoos of similar size and complexity, and certainly nobody can maintain that people of average means cannot afford tattoos – just look at them.

There also is a tendency for men and women who are not artists to belittle their own abilities – I can’t even draw a stick figure, they say. But really, anyone who can write his name legibly has the ability to draw. It is a learnable skill. To attribute it entirely to some intrinsic talent is the excuse of a lazy man who does not want to acknowledge how much practice is involved. A century ago, drawing was a fashionable hobby, particularly among women. And while not a lot of these hobbyists became artists of the first rank, many of them produced work that is as good as that of today’s professionals. There are plenty of opportunities for art lessons today, books and classes both.

What is lacking now, and what many people seem to want, is sound instruction on making specifically religious art. And unfortunately, some of the people who set themselves up as authorities on this are not qualified. I would like to help remedy this; one of my strengths as an artist is that I do a lot of research, and I hope some day to summarize all of the iconographic traditions that I have discovered in an accessible reference book that any amateur or professional artist could use.

An imperfect analogy might be made to culinary art (which may be the one traditional form of art that is really flourishing in the present day). There are some professional chefs working at the highest level of the art, and there are countless men and women cooking at home. These complement each other; the professionals and amateurs are not really competitors, and both benefit from the other making the best food they possibly can. I think that contemporary culinary art owes some of its success to a free exchange of information; a good chef is not afraid to share or publish his recipes; he knows that his imitators are not a threat to him.

I would like to see more religious artists doing the same, reaching out directly to average men and women, and not treating the principles and methods of making good art like secrets. We no longer operate under a guild system that can enforce quality control or fix just prices, so there is no benefit to excluding amateurs from participation in the sacred arts.

9. Where can someone purchase your artwork or learn more about your work?

Most of my recent works can be seen on my website, www.danielmitsui.com. Whatever original drawings or prints I offer for sale can be purchased there. I also have the texts of some lectures I have given which explain my ideas more thoroughly; a newsletter; and some coloring sheets for free download. Anyone interested in a new commission can e-mail me at danmitsui at hotmail.com.

Don’t Miss a Thing

Subscribe to get email notifications of new posts and special offers PLUS a St. Joseph digital poster.

Related

COMMENTS

Reader Interactions

Comments

Trackbacks

-

-

[…] Gregory, epicPew The Couch or the Confessional – Vicki Burbach, Catholic Spiritual Direction Art for God’s Sake: An Interview with Artist Daniel Mitsui – Sam Guzman, The Cthlc Gntlmn Seven (7) Lessons From the Visitation – Debbie Gaudino, […]

-

[…] Источник (англ.): The Catholic Gentleman […]

I love this interview. It reminds me a little of my wife’s style (who tries to synthesize both a Book of Kells style and Syrian iconography). I put it as the website on this post if you want to take a look. She does woodburn, stain and paint for her medium (all three combined, that is). I’m going to show this to her as soon as I get home this evening!

Amazing! Very beautiful style of art… Fitting to display our Faith. 🙂

Daniel Mitsui has a new adult coloring book with Ave Maria Press, The Mysteries of the Rosary, and a second coloring book, The Saints, which will come out in November. https://www.avemariapress.com/product/1-59471-584-X/The-Mysteries-of-the-Rosary/